Sheet Metal Fastening: Methods, Fasteners, and DFM Best Practices

19 min

(AI-generated) Close-up of a sheet metal enclosure fastened with screws and rivet nuts in an industrial assembly workshop

Sheet metal fastening is one of those things that looks simple on a drawing and quietly decides whether your part feels solid, or rattles, strips, or cracks six months later. The material is thin, forgiving in some ways, brutally unforgiving in others. Every hole, thread, and fastener choice leaves a permanent mark on strength, cost, and how painful assembly will be.

From a DFM standpoint, fastening is part of the structure itself.

What Is Sheet Metal Fastening?

(AI-generated) A sheet metal enclosure being fastened with screws and rivet nuts in an industrial assembly workshop

Sheet metal fastening is the mechanical joining of separate sheet metal parts into a functional assembly.

In real fabrication, sheet metal fastening differs from fastening solid or molded parts in several key ways:

● Thin material limits thread engagement, making fastener choice critical to joint strength.

● Tolerances stack up after cutting and bending, so fastening must accommodate real-world variation.

● Fasteners often carry the primary load path, not the sheet itself, especially in thin gauges.

What Sheet Metal Fastening Means in Fabrication and Assembly

In real fabrication, sheet metal fastening usually happens after cutting, bending, and forming, when tolerances stack up, and parts are no longer perfectly flat. That’s where good fastening design shows its value.

Sheet metal fastening methods typically rely on:

● Screws threading into thin material or inserts

● Rivets creating permanent joints

● Clinch or press-fit fasteners added during or after forming

Because the base material is thin, you’re rarely relying on raw material strength alone. The fastener often is the load path. Get that wrong, and no amount of thicker gauge will save the joint.

Why Fastening Choice Affects Cost, Strength, Serviceability, and Lead Time

Fastening decisions often drive hidden costs that are easy to overlook:

● Extra hardware SKUs

● Secondary operations like tapping or insertion

● Slower manual assembly

● Rework when threads strip or holes deform

Sheet Metal Fastening Objectives and Design Priorities

When designing fastening for sheet metal, the priorities are usually very practical:

● Reliable load transfer without tearing the sheet

● Repeatable assembly without cross-threading or deformation

● Minimal secondary ops

● Fasteners that survive real handling, not just CAD stress

If you want a broader overview of sheet metal workflows before jumping into fastening, our intro to sheet metal processing explains the main fabrication steps and how they affect assembly.

On paper, it’s just a hole and a bolt. In the real world, fastening is where most sheet metal assemblies fall apart. Threads strip, panels buckle, and vibration eventually rattles everything loose. Unlike solid blocks, thin sheet metal is unforgiving; if your hole placement or installation order is off, the part will fail long after it leaves the shop.

Fastening problems rarely show up in CAD. They show up in production. At JLCCNC, we treat fastening as a core fabrication step, instead of just an afterthought like some other shops. We bake fastener selection and assembly logic directly into the manufacturing process to catch the warping and stripping issues that ruin parts during final assembly. This guide covers the specific fasteners for sheet metal that actually hold up, and the design blunders that quietly kill long-term reliability.

Common Sheet Metal Fastening Methods

Sheet metal doesn’t fail the way thick parts do. It stretches, dimples, tears, and slowly loosens under vibration. So when you’re choosing a sheet metal fastening method, the real question isn’t “will this hold?”, it’s how it carries load over time, and where that load ends up in the sheet.

Below is how the common methods actually behave in the real world.

Threaded Fastening Methods

(Istock) Self-tapping sheet metal screws

Threaded fasteners are everywhere because they’re familiar and serviceable, but bare sheet metal is usually too thin to hold threads reliably on its own.

That’s why most designs rely on:

● Tapping screws that form threads as they go

● Threaded inserts or PEM nuts that spread the load into the sheet

Threaded joints handle tensile loads reasonably well if the load is shared through an insert or flange. Where they struggle is vibration. Repeated micro-movement slowly works the threads, especially in thin material, until the joint loosens or the hole deforms.

Design reality:

If you’re relying on a single screw biting directly into a thin sheet for anything structural, you’re living on borrowed time.

Riveting and Blind Fastening Methods

(AI generated) Blind rivet being installed into a vertical sheet metal panel using a pneumatic rivet tool.

Rivets are particularly effective in shear-dominated joints, especially compared to threaded fasteners in thin sheet.

Solid rivets, blind rivets, and structural pop rivets clamp the sheets together and transfer load across the joint without stressing threads. There’s no risk of stripping, and vibration resistance is excellent because nothing can back out.

The sacrifice is permanence. Once it’s riveted, it’s not coming apart without drilling. That’s fine for enclosures, brackets, and frames, but terrible for anything that needs servicing.

Design reality:

Rivets are boring, strong, and honest. If you don’t need disassembly, they’re hard to beat.

Clinching and Press-Fit Fastening

(AI generated) Sheet metal clinching process joining two thin metal sheets using a mechanical press in a factory.

Clinching and press-fit fasteners form a mechanical lock by deforming the sheet itself. No threads. No loose hardware during assembly.

These methods are fast and repeatable in production, and they perform well under vibration because there’s nothing to loosen. Load is spread over a formed region rather than concentrated at a sharp thread root.

The downside is tooling and access. You need the right press, correct material thickness, and proper edge distances. Get any of that wrong and the joint looks fine—until it pulls out.

Design reality:

Great for high-volume parts where consistency matters more than flexibility.

Tab-and-Slot and Interlocking Joints

(AI generated) Tab-and-slot sheet metal parts being aligned during assembly without fasteners.

Tab-and-slot joints don’t replace fasteners; they reduce how much work the fasteners have to do.

When designed properly, tabs take shear loads directly through the material, while screws or rivets just clamp things in place. This dramatically improves stiffness and alignment, especially on long bends or panels.

They’re especially useful when:

● Parts need self-fixturing during assembly

● You want fewer fasteners without losing strength

Design reality:

If your design relies only on fasteners for alignment, you’re making the sheet metal fasteners do too much.

Load-Bearing and Shear Considerations

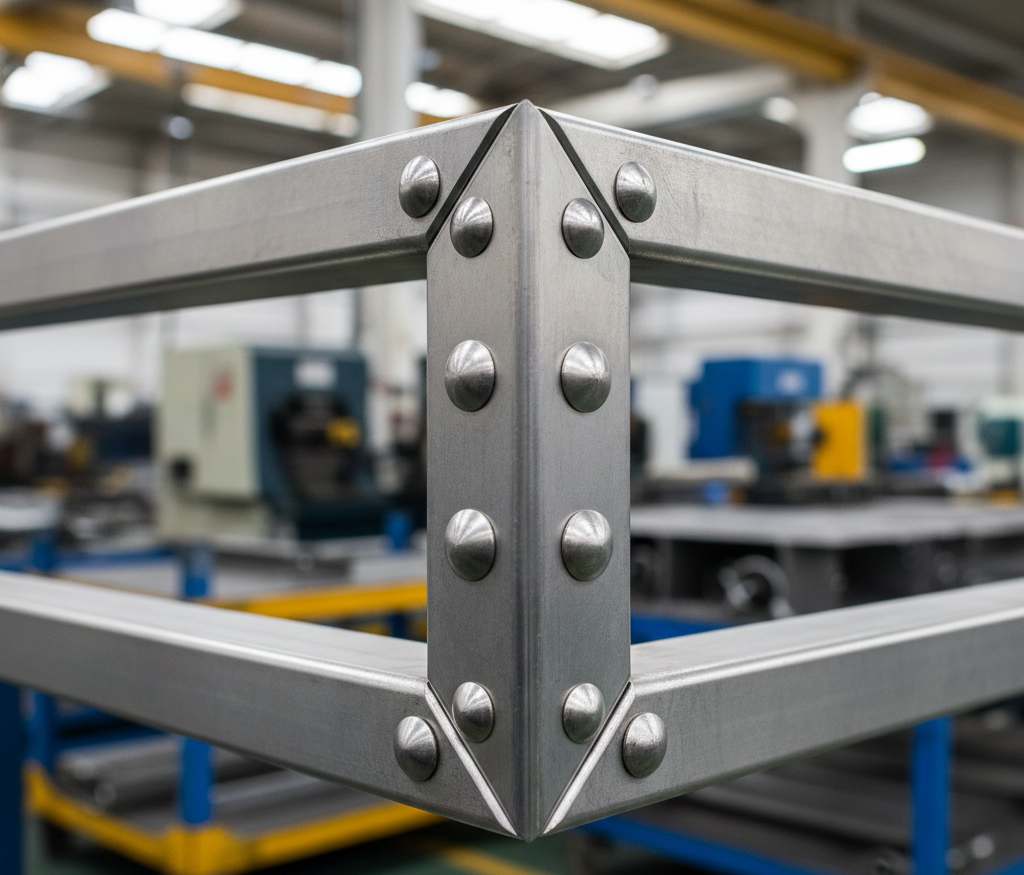

(AI generated) Riveted sheet metal corner joint designed to handle shear loads in an industrial assembly.

In sheet metal, shear is your friend. Tensile loads try to peel fasteners out of thin material, while shear loads let the joint work across a larger area.

Good fastening design:

● Puts fasteners in shear whenever possible

● Uses multiple fasteners to spread the load

● Avoids edge-loaded holes and tight corner placements

Vibration makes everything worse. Joints that look fine on day one slowly loosen unless the load path is clean and the sheet isn’t flexing around the fastener.

If a joint flexes every time the part is handled, no fastener choice will save it.

Fasteners Commonly Used in Sheet Metal Parts

(AI generated) Common fasteners used in sheet metal assemblies arranged on a metal work surface.

Sheet metal fasteners aren’t interchangeable Lego pieces. Each one assumes certain thicknesses, load paths, assembly access, and service expectations. Pick the wrong type and the joint might technically work, right up until it loosens, deforms the sheet, or turns the assembly into a mess.

Here’s how the common options actually behave once they leave CAD and hit the shop floor.

Screws and Bolts for Sheet Metal Assemblies

Screws and bolts are the default choice because they’re familiar and reversible. But sheet metal doesn’t give them much to work with. If you’re using screws, this guide explains the types of sheet metal screws and when each one is appropriate.

In thin gauges, screws usually rely on:

● Thread-forming screws that bite into the sheet

● Machine screws paired with inserts, PEM nuts, or backing hardware

Bare sheet threads wear quickly. A few assembly cycles, a bit of vibration, or slight misalignment during tightening, and the hole starts to oval out. Once that happens, the clamp load drops fast.

Bolts behave better when paired with:

● Flanges

● Washers

● Captive nuts or inserts

Selection reality:

● Good for panels, covers, and serviceable parts

● Weak choice for high vibration or repeated removal unless reinforced

● Almost never ideal as a lone structural solution in thin material

If your design assumes the sheet itself is “holding” the screw, it’s already compromised.

Rivets and Rivet Nuts

Rivets don’t pretend to be flexible. They’re strong, simple, and final.

Standard rivets excel in shear and shrug off vibration because there’s nothing to loosen. They clamp sheets together and distribute the load across the joint instead of concentrating stress at the threads.

Rivet nuts (nutserts) fill a different role. They give you a threaded connection in a thin sheet where tapping isn’t possible. When installed correctly, they spread the load into the surrounding material and make repeated assembly possible.

Where things go wrong:

● Undersized grip ranges

● Too-close edge distances

● Soft sheet paired with oversized rivet nuts

Selection reality:

● Rivets: great for permanent joints and structural seams

● Rivet nuts: useful when you need threads but can’t access the back side

● Both demand proper hole sizing and material thickness

A poorly installed rivet nut spins once, and from that point on, it’s just decorative.

Studs and Captive Fasteners

Studs and captive fasteners are about assembly efficiency as much as strength.

Weld studs, press-in studs, and self-clinching studs create fixed attachment points without loose hardware during final assembly. This speeds things up and reduces dropped parts, especially in vertical or blind assemblies.

They also improve load distribution by anchoring into the sheet over a larger formed area. That makes them more reliable than screws driven straight into thin material.

The trade-offs:

● Added process steps

● Tighter material and thickness requirements

● Harder to modify late in the design

Selection reality:

● Excellent for repeated assembly and production builds

● Strong under vibration when properly installed

● Not forgiving of last-minute design changes

If you care about clean assembly flow on the line, captive fasteners are usually worth the upfront planning.

Fasteners don’t just hold parts together; they define how loads move, how assemblies age, and how painful servicing becomes later. Choosing the “standard” option is easy. Choosing the right one takes a bit more thought, but it saves rework, warranty issues, and a lot of quiet frustration down the line.

If you’re deciding between sheet metal and CNC machining for your part, this comparison highlights the trade-offs in strength, cost, and assembly.

Why Metrics Matter

Sheet metal fasteners don’t usually fail in dramatic ways. They loosen, creep, ovalize holes, or snap after vibration and repeated load cycles. That’s why looking at only “strength” is misleading.

These metrics tell you how a joint behaves in the real world:

● Tensile strength – How much pulling force the fastener can take before failing or pulling out of the sheet. Critical for panels under load or cantilevered parts.

● Shear strength – How well the joint resists sliding forces between sheets. This is the dominant load in most sheet metal assemblies.

● Torque-out resistance – How much tightening force the sheet or insert can handle before stripping or spinning. Especially important in thin gauges.

● Vibration resistance – How well the joint survives real operating conditions: motors, transport, handling, thermal cycling.

● Typical applications – Because context matters more than raw numbers.

The values below are order-of-magnitude, comparative ranges, not datasheet maxima. They’re meant to help you choose between fastening methods, not size a critical safety joint.

Comparative Fastener Performance in Sheet Metal Assemblies

The table below compares common sheet metal fasteners based on real-world performance trends rather than datasheet maximums.

Fastener Type

| Fastener Type | Tensile Strength (N) | Shear Strength (N) | Torque-Out Resistance (Nm) | Vibration Resistance | Typical Applications |

| Self-tapping screw (thin sheet) | 800–1,500 | 600–1,200 | 0.5–1.5 | Low | Light covers, access panels, low-load enclosures |

| Machine screw + PEM nut | 2,000–4,000 | 2,000–3,500 | 2–6 | Medium | Serviceable panels, brackets, and modular assemblies |

| Blind rivet (aluminum) | 1,500–3,000 | 2,000–4,000 | N/A | High | Structural seams, vibration-prone joints |

| Steel blind rivet | 3,000–6,000 | 4,000–7,000 | N/A | Very High | Load-bearing frames, industrial enclosures |

| Rivet nut (steel) | 2,500–5,000 | 2,000–4,000 | 5–10 | Medium | Threaded joints in thin sheet, blind assemblies |

| Self-clinching stud | 4,000–7,000 | 4,000–6,000 | N/A | High | Repeated assembly points, production builds |

| Weld stud | 6,000–10,000+ | 6,000–9,000 | N/A | Very High | Structural attachments, high-load brackets |

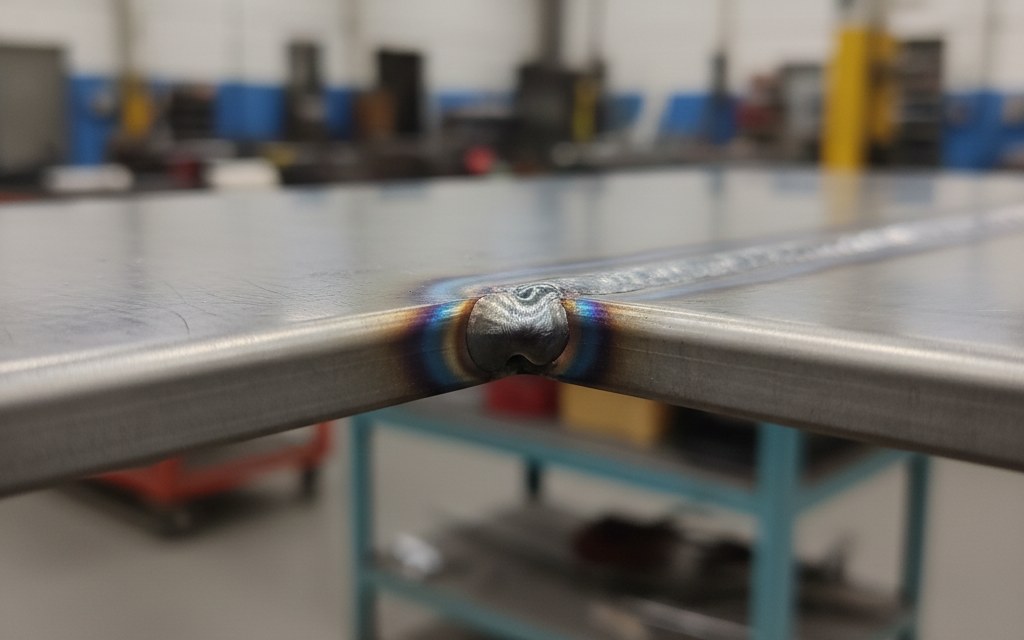

Mechanical Fastening vs Welding and Bonding

(AI generated) Welded sheet metal joint showing permanent bonding and heat-affected zone

Thin sheet metal behaves very differently than thick plate. What works beautifully on a 6 mm bracket can quietly destroy a 1 mm enclosure. This is where fastening choice stops being theoretical and starts being painful.

When Mechanical Fastening Is Preferred Over Welding

Mechanical fastening wins whenever control matters more than permanence.

Thin sheet doesn’t like heat. Welding dumps localized energy into material that has nowhere to dissipate it. The result is distortion, residual stress, and assemblies that never sit flat again. Mechanical fasteners avoid that entirely.

They also make sense when:

● Parts need to come apart later (inspection, upgrades, field repairs)

● Multiple materials are involved (aluminum to steel, coated surfaces)

● Cosmetic surfaces matter and can’t be ground or refinished afterward

In real production, mechanical fastening is often chosen not because it’s “stronger,” but because it’s predictable. You can model it, test it, torque it, and repeat it.

Limitations of Welding and Bonding in Thin Sheet Metal Parts

(AI generated) Adhesive bonding used as a sheet metal fastening method without mechanical fasteners

Welding thin sheet is unforgiving. Even skilled welders fight:

● Warping from heat input

● Burn-through on edges and corners

● Loss of corrosion protection around weld zones

Adhesive bonding avoids heat, but brings its own issues:

● Surface prep becomes critical and easy to mess up

● Cure time slows production

● Inspection is harder, bond failure often isn’t visible until it fails

Bonding can work well for vibration damping and cosmetic panels, but once loads, temperature swings, or long-term service enter the picture, reliability becomes harder to guarantee.

Comparing Durability, Repair, and Reworkability

Fastened joints fail loudly and locally. A loose screw, a pulled rivet, a stripped insert, you see it, fix it, move on.

Welded and bonded joints fail quietly. Cracks propagate. Adhesives degrade. Repairs usually mean cutting, grinding, or scrapping parts entirely.

That difference alone is why mechanical fastening dominates in enclosures, frames, and serviceable assemblies, even when welding looks cheaper on paper.

How to Choose the Right Fastening Method for Sheet Metal

(AI generated) Sheet metal thickness and material considerations when selecting fastening methods

There’s no universal “best” fastening method. There’s only what survives your material, your loads, and your production reality.

Here’s how experienced designers actually decide.

Sheet Thickness, Material Type, and Load Requirements

Start with thickness. It sets the ceiling for everything else.

● Thin gauges limit thread engagement and torque

● Softer materials (aluminum, copper) need load spreading

● Shear loads usually matter more than tensile loads in sheet assemblies

If the sheet can’t safely hold threads, you’re already looking at:

● Rivets

● Clinch fasteners

● Inserts or studs

Trying to force screws into thin material is how joints slowly die in the field.

Material choice changes everything, including stiffness, corrosion, and fastener compatibility. This guide breaks down how to select the right sheet metal material.

Disassembly, Maintenance, and Field Service Needs

Ask this early, not after the prototype.

If a part needs to come apart:

● Screws + captive fasteners beat rivets

● PEM nuts beat tapped sheet

● Welds and adhesives are usually out

Field service changes the math completely. A joint that’s fine in the factory can be a nightmare once it’s covered in dust, vibration, and human impatience.

Cost, Production Volume, and Lead-Time Considerations

Low volume favors flexibility. High volume favors repeatability.

● Screws are cheap upfront but expensive in labor at scale

● Rivets are fast and consistent in production

● Clinch fasteners pay off once quantities climb

Lead time matters too. Specialty fasteners can stall builds just as effectively as missing parts.

Fastener Selection Checklist

Before locking a design, sanity-check it:

● Can the sheet handle the torque without stripping?

● Is edge distance sufficient to avoid tear-out?

● Will vibration loosen this joint over time?

● Can this be assembled consistently on the shop floor?

● Can it be repaired without destroying the part?

If you can’t confidently answer these, the fastening method isn’t finished, no matter how clean the CAD looks.

Fastening issues usually don’t show up in the first build. They show up after a few assemblies, or worse, after parts have already shipped.

Understanding bending and forming technology helps predict how a part will behave once fastened and assembled.

A common case we see at JLCCNC is a sheet metal enclosure designed with self-tapped screws directly into thin aluminum. It works for the prototype. Then production starts, parts get assembled a few times, and threads begin to strip. The fix ends up being inserts or rivet nuts, meaning new holes, revised drawings, and delayed builds.

That’s why fastening decisions are reviewed as part of the fabrication process at JLCCNC, not after. Fastener type, hole sizing, edge distance, and installation order are validated early, so the same part works in prototype, low volume, and scale production.

If a project is moving toward manufacturing and fastening reliability matters, getting a quote early can help lock in those decisions before they turn into revisions.

DFM Tips and Common Sheet Metal Fastening Mistakes

(AI generated) Sheet metal deformation caused by improper fastener edge distance and hole placement

Most fastening problems don’t show up in CAD. They show up on the line, when parts don’t sit flat or threads disappear after one install.

Cutting quality affects edge strength and hole accuracy, this article covers the most common cutting problems and how to prevent them.

Hole Size, Edge Distance, and Deformation Risk

Holes placed too close to edges are a classic failure point. Under load, the sheet doesn’t crack; it stretches, ovals, and slowly tears. Give fasteners room to breathe, especially in thin gauges, and avoid stacking multiple fasteners along a weak edge.

Thread Stripping in Thin Sheet Metal and Better Alternatives

Bare threads in a thin sheet rarely last. One over-torque or reassembly and they’re gone. If the joint matters, switch to clinch nuts, rivet nuts, or studs early instead of trying to “be careful” during assembly.

Fastener Installation Order and Finishing Sequence Considerations

Fasten before finishing whenever possible. Powder coating and plating add thickness, change friction, and can throw off torque. Installing fasteners after finishing also risks chipped coatings and cosmetic rejects.

Avoiding Assembly Conflicts and Interference

Clearance gets forgotten fast. Tools need space, fingers need space, and stacked tolerances add up. If a fastener can’t be installed straight, it won’t survive long.

Typical Applications of Sheet Metal Fastening

Mechanical fastening shows up anywhere parts need to be strong, serviceable, and repeatable.

Enclosures, Panels, and Electronic Housings

Fasteners allow access without destroying the part. That’s why screws, inserts, and captive hardware dominate control boxes, racks, and covers.

Brackets, Frames, and Structural Assemblies

Here, shear strength and vibration resistance matter more than looks. Rivets, studs, and bolted joints handle load without warping thin material.

Automotive, Aerospace, and Industrial Equipment Applications

These environments punish bad fastening choices. Vibration, heat cycles, and repeated service make predictable, mechanically locked joints the safest option.

All in All

Designing reliable sheet metal assemblies comes down to choosing fastening methods that match the material, the load, and how the part will actually be used. When those decisions are rushed, problems show up fast, usually after production has already started.

If you’re working on a sheet metal project and want fastening, fabrication, and assembly handled consistently from the start, JLCCNC offers end-to-end sheet metal fabrication services with integrated fastening support. Quotes are fast, pricing is competitive, and even low-volume builds are welcome.

FAQ

What is the best fastening method for thin sheet metal?

There isn’t a single “best” method. For a thin sheet, mechanical fastening usually works better than welding because it avoids heat distortion and allows rework. Screws with inserts, rivets, and clinch fasteners are common choices, depending on load and service needs.

Is mechanical fastening better than welding for sheet metal?

Mechanical fastening is better than welding for sheet metal when heat distortion, surface damage, or future disassembly must be avoided. Welding is still preferred for permanent, high-rigidity structural joints.

What fastener works best for vibration-prone sheet metal assemblies?

Blind rivets, self-clinching fasteners, and weld studs perform best in vibration-prone sheet metal. For threaded joints, PEM nuts or rivet nuts with locking features are recommended.

Why do threads strip so easily in sheet metal?

Because the thin sheet doesn’t provide enough thread engagement, even moderate torque can deform the material instead of clamping it. Using clinch nuts, rivet nuts, or studs spreads the load and dramatically improves reliability.

Are rivets stronger than screws in sheet metal?

In many cases, yes, especially in shear and vibration. Rivets don’t rely on threads in thin material, which makes them more stable over time. The trade-off is reduced serviceability.

When should I avoid welding sheet metal parts?

Welding becomes risky with thin gauges, cosmetic surfaces, or tight flatness requirements. Warping, burn-through, and post-weld rework often outweigh the perceived strength benefits.

How do I prevent fasteners from loosening under vibration?

Design for shear, not friction. Use proper fastener spacing, avoid oversized holes, and consider mechanical locking methods or rivets instead of relying on torque alone.

When does outsourcing sheet metal fastening make sense?

If fastening quality varies, assemblies slow down production, or rework starts stacking up, outsourcing can help. Manufacturers like JLCCNC integrate fastening and assembly into the fabrication process, improving consistency while keeping costs predictable.

Popular Articles

• 9 Sheet Metal Cutting Problems and Solutions

• Hole cutting in sheet metal: techniques, tolerances and applications

• Introduction to Sheet Metal Processing: Techniques and Tools for Precision

• Bending and Forming Technology in Sheet Metal Processing

• Laser cutting technology in sheet metal processing

Keep Learning

MAG Welding: Process, Advantages, MIG Comparison, and Applications

(AI generated) MAG welding process on steel sheet metal using active shielding gas in an industrial fabrication workshop The MAG welding (Metal Active Gas welding) process uses a continuously fed wire electrode and an active shielding gas that participates in the arc chemistry, which distinguishes it from other welding processes. The active shielding gas distinguishes MAG welding from MIG welding, contributing to its superior performance on carbon steels and low-alloy steels. MAG welding is widely use......

CNC Turret Punching: How It Works, DFM Guidelines, Cost & Services

(AI generated) CNC turret punch press operating in a sheet metal fabrication workshop. Turret punching can produce holes and formed features efficiently; however, part quality and cost depend on material selection, tooling condition, and process planning. For enclosures or panels with many repeatable features, turret punching is often faster and more cost-effective than laser cutting, provided the geometry, material, and tolerance requirements match the process capabilities. This guide explains how CN......

Sheet Metal Fastening: Methods, Fasteners, and DFM Best Practices

(AI-generated) Close-up of a sheet metal enclosure fastened with screws and rivet nuts in an industrial assembly workshop Sheet metal fastening is one of those things that looks simple on a drawing and quietly decides whether your part feels solid, or rattles, strips, or cracks six months later. The material is thin, forgiving in some ways, brutally unforgiving in others. Every hole, thread, and fastener choice leaves a permanent mark on strength, cost, and how painful assembly will be. From a DFM sta......

Expanded Metal Sheet Guide: Sizes, Applications & Manufacturing Insights

(AI-generated) Expanded metal sheets are a foundational material across modern manufacturing, construction, architecture, transportation, and energy industries. They are created by mechanically slitting and stretching a solid metal sheet into a uniform mesh, rather than punching holes, welding wires, or weaving strands. This unique process preserves material continuity while creating openings that reduce weight, improve airflow, and enhance functional performance. Unlike perforated, welded, or woven m......

Guide to Sheet Metal Screws and Different Screw Types

What Are Sheet Metal Screws? (iStock) A technician fastening self-tapping screws into an aluminum sheet in an industrial workshop. For thin-gauge assemblies where you can't fit a nut and bolt, sheet metal screws are a reliable way to achieve sufficient clamping force in thin-gauge sheet metal”. Because they're case-hardened, they form their own mating threads in the substrate. This creates a much tighter interface than a wood screw ever could, making them ideal for enclosures or housings that deal wit......

Rivet Guide: What Is a Rivet and How to Remove Rivets Properly

Rivets are one of the oldest and most reliable methods for joining metal parts. Even with modern welding and adhesives, riveting continues to be valued for its simplicity, strength, and consistency — especially when heat or distortion must be avoided. But what is a rivet, and how does it function in sheet metal assembly? A rivet is a cylindrical fastener with a head on one end and a tail on the other. When inserted into aligned holes, the tail is deformed using a riveter, creating a permanent mechanic......